History of Maine Tourmaline

First Discovery

1820 was one of the most important years in Maine’s history. In that year, Maine was granted statehood and became the 23rd state in the United States of America. In that same year, tourmaline was discovered in the mountains of western Maine.

Augustus Choate Hamlin, son of Elijah Hamlin, one of the original discoverers, spent most of his life exploring Mt. Mica in search of treasures hidden there. He also carefully documented the work of his father, as well as his own and others, and his History of Mount Mica, published in 1895 gives us a complete account of the original discovery – in a description so vivid it is truly a link back in time, to that autumn of 1820. His work is gratefully acknowledged as the major source of our information concerning the discovery of tourmaline in Maine.

This discovery was made by two students who had become interested in mineralogy, and who spent much of their leisure time searching for minerals among the exposed ledges and mountains around the village of Paris, Maine.

Late in the autumn of 1820, and on one of its clear, calm days, Elijah Hamlin and Ezekiel Holmes started out to explore the range of hills which formed the eastern boundary of the town of Paris, and which stretch away to the northwest.

They had spent most of the day on Mount Mica, part of the mountain ridge to the south of the village, and were descending the  western declivity on their way home, just as the sun was setting behind the great White Mountain range, fifty miles or more away on the western horizon. Young Hamlin hesitated for a moment on the crest of a hill to enjoy the entrancing scene which spread before him, and on turning to the east for one final look at the woods and mountains behind him, a vivid gleam of green flashed from an object on the roots of a tree upturned by the wind, and caught his eye.

western declivity on their way home, just as the sun was setting behind the great White Mountain range, fifty miles or more away on the western horizon. Young Hamlin hesitated for a moment on the crest of a hill to enjoy the entrancing scene which spread before him, and on turning to the east for one final look at the woods and mountains behind him, a vivid gleam of green flashed from an object on the roots of a tree upturned by the wind, and caught his eye.

Advancing to the spot, he found a transparent green crystal lying loose upon the earth which still clung to the root of the fallen tree. The student clutched the glistening gem with eagerness, and called back to his companion, who had already passed over the brow of the hill, and was some distance down the slope. After examining the newly found treasure, the students carefully searched among the surrounding soil for other specimens; but the rapidly increasing twilight soon compelled the youthful mineralogist to abandon the search. They, however, resolved to return early the next morning and continue the exploration, but during the night a storm arose, and covered the hill and its adjacent fields with a thick mantle of snow which remained until the next spring.

As soon as the winter’s snow has melted away, and left the hill and its sides exposed to view, the students again returned to the search, and this time with success. They went directly to the bare ledge which crops out on the brow of the hill, and which they had not examined on their previous visit, before darkness had overtaken them. As they climbed up over the rock, they were astonished to observe many crystals and fragments of crystals, lying loose upon the bare ledges and sparkling in the rays of the sun. These they carefully gathered; and tracing others to the earth below the ledge, and which had formed from the decomposition of the rock, they eagerly turned up the soil in search of hidden treasure. Thirty or more crystals of remarkable beauty and transparency rewarded the labors of the students, and with mingled feelings of joy and wonder they held them up to the rays of the sunlight, and admired their various shades of green, red, white, and yellow in different shades. They had, indeed, stumbled upon one of the richest and rarest of nature’s laboratories.

News of the discovery spread to the villagers and many of them hastened to the spot and secured a number of fine specimens as trophies or mementos, yet the exact nature of the discovery was still unknown, even to the original discoverers. A few specimens were sent to Yale University Professor Benjamin Silliman, and were only then first identified as tourmaline. Descriptions of the earliest gems were published by Hamlin in 1826, revealing his skill as a competent amateur mineralogist. In 1822, Hamlin’s younger brothers, Cyrus and Hannibal (Later Vice President to Abraham Lincoln) then scarcely in their teens, borrowed some blasting tools, made a crude blast, and opened a cavity in the solid ledge, searching for crystals beyond those originally found on the surface, or by superficial digging. Their efforts were greatly rewarded, with some of the largest and at that time, finest quality specimens yet discovered. They collected more than twenty crystals of various greens and red colors, some larger than two inches long and an inch in diameter.

News of the tourmaline discovery circulated rapidly, and Mt. Mica soon came to be known as the foremost site in North America for minerals of such great variety and richness.

Tourmaline has been mined in Maine now for nearly 200 years, and yet today, Mt. Mica is still considered to have the greatest potential for additional production of crystals and gemstock. Major discoveries have been made there as recently as 1978, when, in a grapefruit-sized cavity, was found a remarkable piece of gem quality crystal – one of the stones cut from it was a magnificent 256 carat flawless blue-green gem, which is 4-5 times larger than the previous “biggest-best” gem from this locality.

1972 – A World Class Discovery

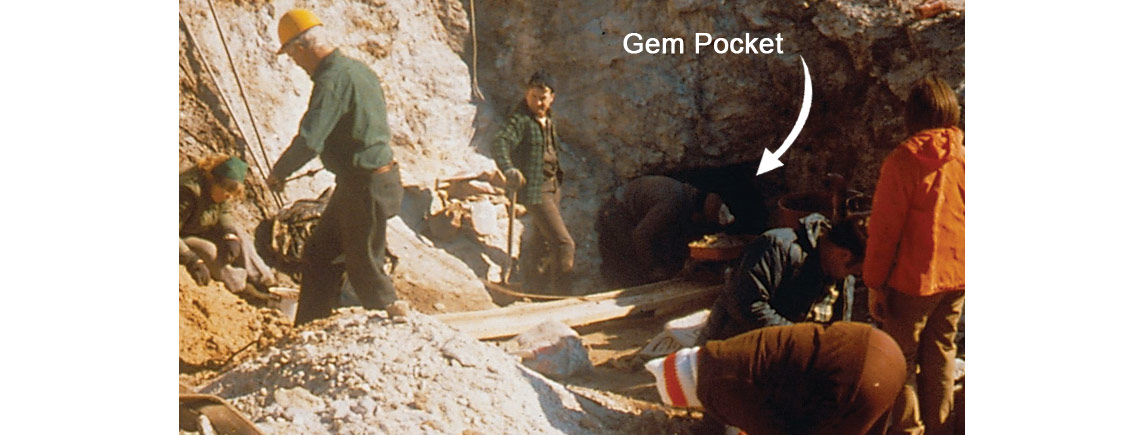

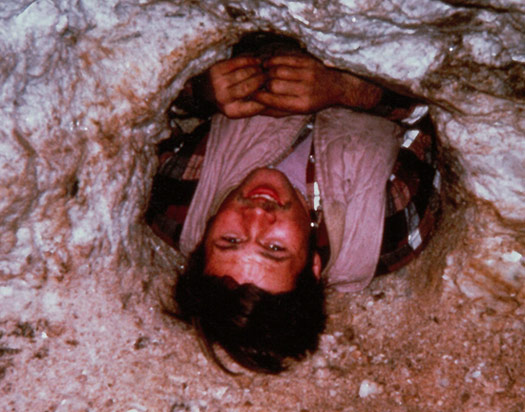

Plumbago Mountain was the site of a discovery in 1972, which is now recognized as the largest gem find in North America. The now-famous discovery was made by George Hartman, Dale Sweatt and James Young in August, 1972, and following some preliminary mining and exploration, the Plumbago Mining Corporation was organized by Hartman, Sweatt, and Dean McCrillis. They obtained a lease from the International Paper Company, Frank Perham was hired, and exploration for gem tourmaline was resumed, which resulted in October, 1972, with opening a series of pockets that proved to be richer than any previously discovered in Maine, and perhaps anywhere in the world.

The mining operations on Plumbago Mountain continued through 1974, and details of the early finds are available through the vivid descriptions found in Dean McCrillis’ daily log: