History of Mount Mica

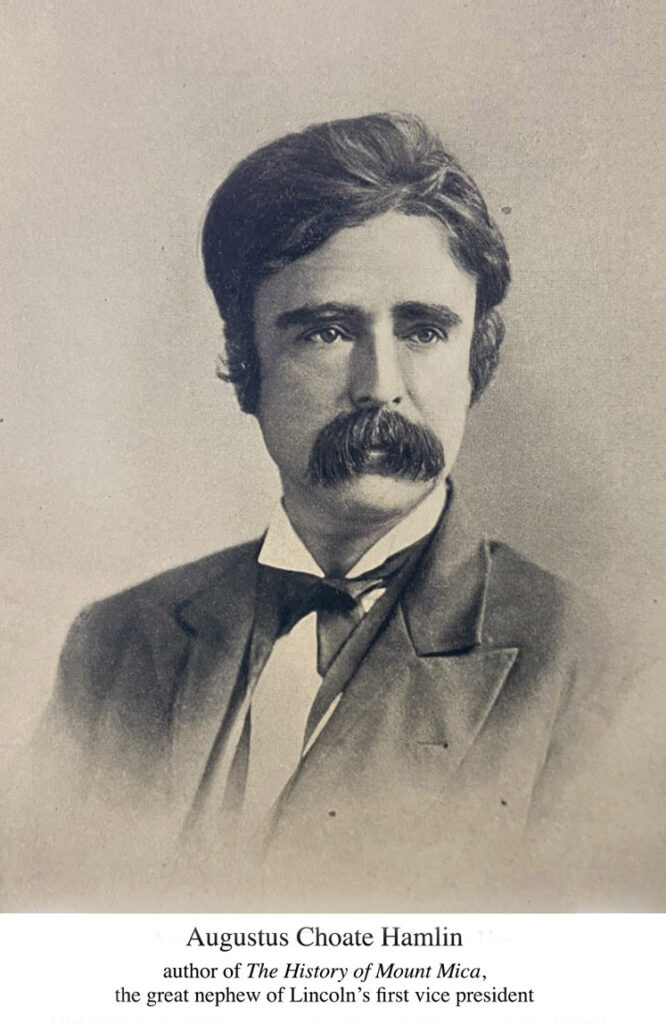

The following is an excerpt from The History of Mount Mica by Augustus Choate Hamlin, published in 1895:

MOUNT MICA is situated in Paris, the shire town of Oxford County, in the state of Maine. The village is one of those quiet, secluded places, enriched by political and scientific tradition, and adorned with scenes of great natural beauty, which the poet and the philosopher seek for, and cherish when found.

A mile or more to the eastward of its court house, at the foot of the slope of a mountainous ridge which like a great mural wall hides the eastern horizon from view, appears a little hill seeming to be one of the buttresses of the rocky range towering above it. This little hill, with its great gray piles of broken rocks, which have been torn from its surface by the explorations of more than half a century, disfiguring its natural beauty, is the famous Mount Mica, known to every mineralogist of note in the scientific world, and dear to every heart that loves and respects the beautiful and the mysterious among nature’s works.

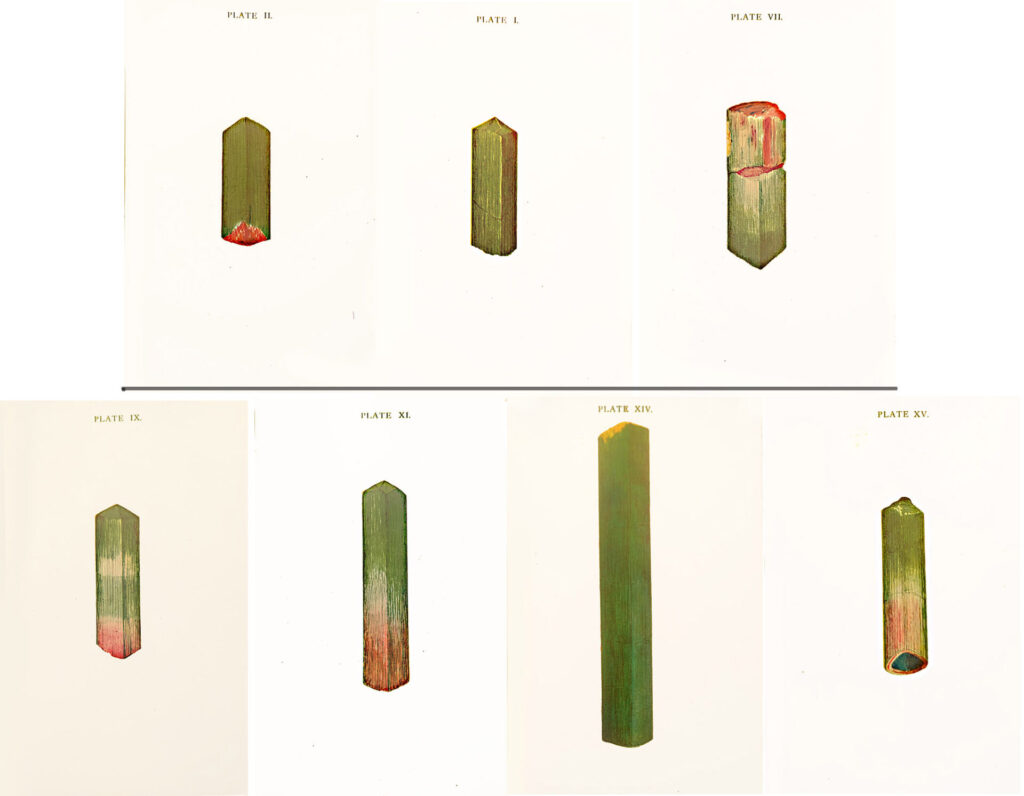

It was discovered in 1820 by two students who had become interested in the study of mineralogy, and who spent much of their leisure time in searching for minerals among the exposed ledges and the mountains around the village. Late in the autumn of 1820, and on one of its clear, calm days, they started out to explore the range of hills which form the eastern boundary of the town and stretch away to the northwest, until lost among the mountains around Molly Ocket. The names of these two students were Elijah L. Hamlin and Ezekiel Holmes. Hamlin was a resident of the village, but Holmes was a visitor, and temporarily a student, in the place. They had spent most of the day along the mountain ridge to the southward and were descending the western declivity on their way home, just as the sun was setting behind the great White Mountain range, fifty miles or more away on the western horizon. At this moment the view of the intervening country, diversified in color and in shade, together with the gorgeous masses of changing clouds in the western sky, formed a picture of great beauty, and young Hamlin, fascinated with the entrancing picture spread before him, halted for a moment on the crest of a little knoll to enjoy the scene. On turning to the eastward for an instant for a final look at the woods and mountains in his rear, a vivid gleam of green flashed from an object on the roots of a tree upturned by the wind, and caught his eye.

Advancing to the spot, some rods in his rear, he perceived a fragment of a transparent green crystal lying loose upon the earth which still clung to the root of the fallen tree. The student clutched the glistening gem with eagerness, and called back his companion, who had already passed over the brow of the hill, and was some distance down the slope. After examining the newly found treasure, the students carefully searched the surrounding soil for other specimens; but the rapidly increasing twilight soon compelled the youthful mineralogists to abandon the search. They, however, resolved to return early in the morning and continue the exploration. But during the night a storm arose, and covered the hill and its adjacent fields with a thick mantle of snow, which remained until the next spring.

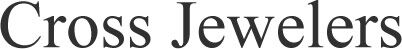

As soon as the winter’s snows had melted away, and had left the hill and its sides exposed to view, the students again returned to the search, and this time with success. They went directly to the bare ledge which crops out on the brow of the hill, and which they had not examined on their previous visit, before darkness had overtaken them. As they climbed up over the smooth and denuded surface of the rock, they were astonished to observe many crystals, and fragments of crystals, lying exposed upon the bare ledge, and sparkling in the rays of the sun. These they carefully gathered; and tracing others to the earth below the ledge, and which had formed from the decomposition of the rock, they eagerly turned up the soil in search of its hidden treasures. Thirty or more crystals of remarkable beauty and transparency rewarded the labors of the students, and with mingled feelings of joy and wonder they held them up to the rays of the sunlight, and admired their varied colors of green, red, white, and yellow in different shades. They had, indeed, stumbled upon one of the richest and rarest of nature’s laboratories. All around the brow of the ledge, enormous masses of rose red lepidolite, splendid groups of crystalized quartz of white or of smoky hues, black crystals of the oxide of tin, broad foliae of glistening mica, snowy flakes of feldspar, studded with minute transparent crystals of green and red tourmalines, lay scattered about in profusion. Collecting as many of the choice and beautiful specimens as they could carry, the students, heavily laden, returned to the village, and sought to ascertain the nature of their mineral treasures. Subsequent examination indicated that the ledge was perforated with cavities, in which the tourmalines and other minerals had been deposited. It was also evident that the crystals that had been gathered by the students had been set free from their cavities by the decomposition of indefinite periods of time, which had disintegrated the surface of the ledge. There was no evidence of drift; and the crystals lay exposed upon the rock, while the softer and more perishable materials had been set free and washed by the rain, and blown by the winds, down to the base of the ledge, and accumulated in time as soil. Parts of the ledge yet exposed to view were fairly honeycombed with small cavities and soft spots, where the decomposing feldspar was crumbling away. In these cavities and decayed places in the rock, other tourmalines were obtained by breaking away the edges of the cavities, or removing the decomposed material.

The discovery having been made known to the villagers, many of them hastened to the place, and secured a number of fine specimens as trophies or as souvenirs. As no one in the vicinity was able to distinguish the character or nature of the specimens, or even to call them by name, the students enclosed a few of the smaller crystals in a letter to Professor Silliman, of Yale College, and requested him to describe them. He kindly and promptly informed the youths that the minerals were tourmalines, and of rare occurrence. Thereupon the students selected some of the finest and purest of the crystals and addressed them to the professor, in return for his kindness. The parcel was entrusted for safe keeping to the late Governor Lincoln, who was then a member of Congress, and about to start for Washington. At this period the journey to the capital was a serious undertaking, and the condition of the roads was such that most of the distance had to be traversed on horseback. The Governor started safely with the precious package, but lost it before reaching New Haven, and no trace of it has ever been found.

Two years after the discovery, the two younger brothers of the discoverer, Cyrus and Hannibal Hamlin, although scarcely in their teens, resolved to make a more complete exploration of the ledge. Having borrowed some blasting tools in the village, they proceeded to the hill and managed in a rough way to drill several holes in the ledge and blast them out. These operations, though of trivial magnitude, were attended with unlooked-for results, for the explosions threw out, to the astonishment of the boys, large quantities of bright-colored lepidolite, broad sheets of mica, and masses of quartz crystals of a variety of hues. The last blast exposed a decayed place in the ledge, which yielded readily to the thrusts of a sharpened stick or the point of the iron drills. As the surface was removed, great numbers of minute tourmalines were discovered in the decomposed feldspar and lepidolite. The rock became softer and softer as the boys proceeded in their work of excavation, and soon they reached a large cavity of two of more bushels capacity. This hollow place, or rotten place, appeared to be filled with a substance resembling sand, loosely packed. Amongst this sand or disintegrated rock, crystals of tourmaline of extraordinary size and beauty were found scattered here and there in the soft matrix. Scratching away with the renewed energy, the boy soon emptied the pocket of its contents, and found that they had obtained more than twenty splendid crystals of various forms and hues. One of these was a magnificent tourmaline of a rich green color and a remarkable transparency. It was more than two inches and a half in length by nearly two inches in diameter, and both of its terminations were finely formed and perfect.

Several other possessed extraordinary beauty, and some of them were quite three inches in length and an inch in diameter. The colors of these tourmalines were quite varied, but were chiefly red and green, and equaled if they did not surpass in beauty the crystals previously collected by their brother Elijah. The exact number of crystals obtained by the boys is not known; but when collected together, with the fragments of others, they filled a basket of nearly two quarts capacity. Besides the tourmalines, the quantity of lepidolite, mica, and other choice minerals thrown out by the blasts or found in the sides of the cavity was so great that the boys were obliged to seek for an ox-team to transport them home. So little was known of the value of these rare minerals at that time that the possessors considered the finest of their treasures to be worth about a guinea. Cyrus afterwards learned from his brother Elijah, who had moved to the eastern part of the state, the names of mineralogists in the United States, and also in Europe, who had made inquiries of him concerning the discovery of Mount Mica, and the disposition of its minerals. With some of these he placed himself in correspondence, and from time to time disposed of nearly all of the finest of the crystals in exchange for money or for minerals.

Cyrus not long afterwards moved to Texas, where he died many years ago, and with him has perished the history and the distribution of these remarkable crystals and gems. The younger brother and survivor, the late Vice President Hannibal Hamlin, took but little interest in mineralogy, and gave his share to his brother Cyrus. He remembered, at the time of the publication of the treatise on the tourmaline, in 1873, only the facts of the discovery, the curious and symmetrical forms, the perfect limpidity and the wonderful beauty of the crystals.

This is all that is known of the history of the splendid gems and the remarkable crystals that Mount Mica yielded to the explorer in its early and best days. Gathered then in profusion, and carelessly treasured, they have since been scattered over the world, and in many instances their identity has been completely lost.

We show seven of the forty-three sketches that are printed in the book.