Damariscotta’s Oyster Bay

And the Thousand-Year Party

It was the biggest party the Maine coast had ever seen. Thousands came every summer. It was wild. June, July, and August, full sun, two tides a day, a full moon every month.

The Thousand Year Party

There was dancing. There was conversation. There was fine dining and bonfires late into the night. It wasn’t just weekends because weekends wouldn’t be invented for two thousand years. It was every night. There were tests of strength. There was competition. There were even fights between tribes because everyone in their teens and twenties was looking for a mate.

There was hunting that thinned out into the forests that surrounded what someday would become Damariscotta and Newcastle, Oyster Bay, Damariscotta Falls, and the Damariscotta River. The party was wild. It was non-stop. There was fishing, swimming, diving, and then there was the lead item on the menu…oysters.

An Ancient Oyster Bar

This wasn’t J’s Oyster Bar on the waterfront in Portland. It was miles of ancient establishments and Stone Age encampments. It was like Burning Man for 90 days but better, and it went on every summer in fog, rain, or shine. How their early commerce worked, we have no idea. There were no coins or credit cards. Money wouldn’t be invented anywhere in the world for over a thousand years, and yet, the party went on every summer for a thousand years. It was never canceled, and in everyone’s lifetime, they made time to attend at least once…often, many times.

We have no idea of the details of what went on. How do we know about the thousand-year party? How do we know it ever occurred? What evidence do we have three thousand years later that the biggest, most successful gathering happened on this spot on the Maine coast? The proof was the Whaleback Shell Heap.

This was the largest shell heap ever found in Maine. Billions of oyster shells were piled on either side of the Damariscotta River above today’s town of Damariscotta. It was an astounding mountain of oyster shells piled up by diners and partygoers at the big event. The Whaleback Shell Heap was the evidence of the success of this oyster feast and this summer festival.

Now, the Archeologist Speaks

The Damariscotta, Newcastle, Maine shell Heaps were astounding for their size. The success of the party was clear even thousands of years later. Excavations have shown oyster shells approaching the size of dinner plates.

Chickens and a company in Boston were responsible for the disappearance of the mountain of shells called Whaleback. Chickens lay eggs. The shell of the egg is mostly calcium. To ensure strong eggs, chicken feed is often supplemented with finely ground ocean shells to reinforce a proper calcium intake for chickens. A Boston firm in the late 1800s saw a goldmine of shells at Whaleback. They paid a local landowner a sum and proceeded to mine the site.

This is an old photo of mining shells at Whaleback.

The Boston company did such a good job mining. Today, you would never know this section of the Damariscotta River, as viewed from old Route One on the Damariscotta side, ever held this historic cash of oyster shells. The State of Maine purchased the land. There is a parking lot up along old Route 1 for 12 cars, and there are signs and pathways that lead down to the riverbank.

The signs explain the historical significance of Whaleback. The signs say nothing about the thousand-year party. At the river’s edge, you can see evidence of soil and shells. If you go to the far right, where the fields stop, and the forest begins, you can see more evidence of larger oyster shells mixed in with the underlying soil.

The Newcastle shell heap

More telling of what Whaleback looked like 150 years ago is looking across the Damariscotta River to Newcastle because the white mounds of shells still spill out of the woods on the Newcastle side and reach down to the river’s edge. Looking upstream, above the new Route One, is Great Salt Bay. This was called Oyster Bay three thousand years ago and is the basis for the name of our necklace and earrings.

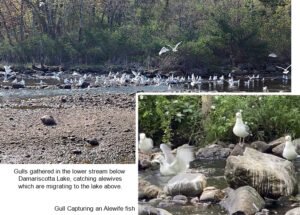

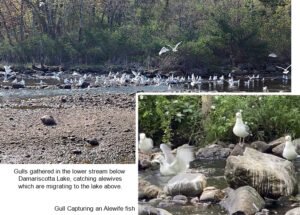

Today, we have two festivals in the area. They are well-attended and are among the best in the country. The first festival is a weekend in the spring at Damariscotta Mills for the annual Alewife Run, where a million Alewives migrate from Salt Bay/Oyster Bay up to Damariscotta Lake. This is a big migration festival attended by thousands over one spring weekend. Food, music, things to buy, people, eagles, gulls, herons, and osprey all come to watch the 10-inch fish leap up the falls to the lake 80 feet above.

Damariscotta & Two Contemporary Festivals

The other event in the area is Damariscotta’s Pumpkin Festival, the first weekend in October. Maine Street in downtown Damariscotta is lined with 50-100 monster pumpkins carved and decorated in an annual contest. There is a pumpkin regatta…monster pumpkins hollowed out, fitted with small outboard motors, and entered into a race on the Damariscotta River. There are pumpkin throwing contests. It’s a wild weekend festival with music, food, and fun. The Damariscotta Pumpkin Festival is considered one of the all-time best festivals in the country.

I’ve been to the Alewife Migration Festival. I’ve been to Damariscotta’s Pumpkin Festival, and I’ve been to the Whaleback Oyster Shell Heap. And the location of the thousand-year party. And while our Oyster Bay sapphire and diamond series has a silent presence with a sparkling blue sapphire and two twinkling diamonds, the sapphire represents the saltwater bay, and the two diamonds represent the guy and gal who meet there and their enduring relationship.

The Gems

Blue sapphire – Blue sapphire usually comes from Southeast Asia. It’s a color nature feels generous with in this part of the world. We love blue, particularly blue that shows well after the sun goes down. We tend toward a lighter brighter true blue color in all of our sapphire pieces.

Diamonds – world sourced, cut in Belgium. Well-cut with a full complement of 58 facets, rating a 3 on our quality cut scale. Nice white color, beautifully matched. Hardness 10.

About the Trade Wind Collection:

Where does inspiration come from? Where do the creative sparks for design begin? For Cross’ new Trade Wind Jewelry Collection, we find ourselves drawn into the story of Captain John Henry Drew, from Gardiner, Maine. Born in 1834, he grew up the son of a Ship’s Carver, and went to sea at the age of 15, eventually becoming Captain of a series of clipper ships, and traveling from New York to China and back home, when that voyage took more than seventeen months.

Instead of carving or knotting or other hobbies that were characteristic of sailors, this mostly self-educated man read books, memorized details from newspapers, and wrote about his journey—his literal and his inner journey. His hand-written and personally illustrated journals tell us of his longing for Maine, for his family, and for “making something of himself”. He is very much like you and me, and it makes his story that much more compelling. He savors apples from home, as tasting better than apples from anywhere else. He imagines the scene he might see looking in the window at home, where his family sits, and he chastises himself for not getting more done at home when he was there.

The jewelry in our Trade Wind Collection is made by his great-great-great grandson, Keith. This young man went to sea as well, at age 18. As part of his service to the US Navy, his travels took him to many of the same places his great-great-great grandfather’s clipper ships visited. Keith also had a hobby unconventional for sailors— he had a fascination for gems and he studied gemology. He studied so that when his service was completed, he could become a jeweler. As Keith traveled the world, he collected exquisite gems, and after leaving the service and returning home, he mastered the art of fine jewelry making.

It is now decades later. We met Keith for the first time in March, 2014. We were impressed with his jewelry, and as we talked further, discovered he had a clipper ship sea captain ancestor and became intrigued with the parallels of his journey in life with that of his sea captain forebear.

The parallels in the two stories are expressed in the jewelry itself—the exotic colors, the flow of the designs, the attention to detail which is something passed down in this family—whether it is to protect the ship, its cargo and its crew, or to create a design that will last and protect its valuable gems, giving the wearer the same pleasure we experience when a ship at full sail goes by. You can’t help but stop and exclaim, “Isn’t that beautiful?”

We were hooked by this story, and by the jewelry. We think you will be too. In fact, we’re posting pages from Captain Drew’s journals from the Voyage of the Franklin in 1868. Take a few minutes to join in the journey, and think of those you love most, and rejoice if they are right there with you.

Read the Captain’s

Clipper Ship Journal Entries

Read Keith’s Gem Expedition Dispatches